Rotary Matching Grant

During the summer of 2008, the Greenville Noon Rotary Club in partnership with the Rotary Club of Dharamsala (India) received a matching grant of almost $10,500 from the Rotary Foundation for a rural health project in northern India (Himachal Pradesh). The funds are being used to help to provide health services, care and immunization to internally displaced peoples in remote areas near Dharamsala. Under the terms of the matching grant, an equal amount of funding was provided by Rotary District 7720 in conjunction with the Greenville Noon Rotary Club and its partner club in India. The total award is over $22,000. The team from the Greenville Noon Rotary Club comprises Dr. Sylvie Debevec Henning (ECU International Studies), Dr. Harry Adams (ECU Brody School of Medicine) and Dr. Ed Davis (Greenville pediatrician). The team from the Dharamsala Rotary Club includes Ashwani Sharma, Virinder Singh Parmar and Rakesh Sharma. We are also working with a community partner, the Tong-len Charitable Trust in Dharamsala, through our ECU liaison Dr. Derek Maher (ECU Religious Studies).

BACKGROUND

Tong-len Charitable Trust

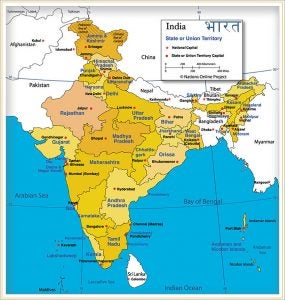

Established in 2004, the Tong-len charitable Trust in Dharmsala, India, is the only non-governmental organization of its type in Himachal Pradesh, a mountainous state nearly as large as West Virginia and home to more than six million people. This organiztion has grown out of the Tibetan refugee community in northern India that is also home to the Dalai Lama. Tibetan people, grateful for the welcoming reception they hae received in India, have noticed people in their midst that are even more in need of assistance. The Tibetans’ experience as refugees in India enables them to approach this work with great sensitivity to local customs and in an effective fashion. Its motto is “Compassion in Action.” Last year the Greenville Noon Rotary provided some support for Tong-len’s Wound Care Clinic through its Pancake Breakfast Fund.

Identified Needs in the Health Status of Displaced Populations

Tong-len works exclusively with displaced communities in Himachal Pradesh to provide support in accessing services and in improving opportunities for education, employment and healthcare. At present its work is focused on the community known as Charan Khad, which is a slum settlement of over 700 people in Lower Dharmsala. The majority of residents are displaced families from rural areas of Rajasthan, although there are also small communities from Maharashtra and Punjab. Most familiies have been living in Charan Khad for 15-20 years, although some have settled there in recent years. In their home regions, these families worked as cattle herders and agricultural laborers, but were driven to hardship by changes in the environment and economy–land dried up and markets shrank as there became less room to compete with growing agri-businesses. At this time, families sought opportunities in different parts of India, eventually settling in Dharmsala, which seemed like a growing and prosperous region where there was potential to earn an income. Unfortunately for many families, Dharmsala can provide little more than the basics for survival. People have no land rights and cannot build; they are forced to live in temporary shelters constructed of bamboo poles and plastic sheeting. They have few welfare rights, and struggle to access any kind of government subsidies that the poor in this region are entitled to. Still, however, this remains a preferential option to their prospects in their home regions, where only insecurity and hunger await them. Conditions within the settlement are very poor. There is no sanitation and the water supply is completely inadequate. Garbage is strewn everywhere as there are no facilities for disposal or collection. Unemployment within Charan Khad is high. No one has a steady income or permanent job. Some of the residents work as shoe shiners or balloon vendors, others as construction laborers. A few of the women and young girls sell bangles and bindis by the side of the road, but the majority scrape a living through the collection and sale of recyclable rubbish. Many of the women and children beg in the streets of McLoad Ganj. All of the work is seasonal, temporary and inadequate to meet their real needs. Many suffer from ill-health that goes untreated because, on the one hand, they cannot afford medication, and on the other, because they are marginalized and often poorly treated within Indian society, accessing support and institutions is difficult. Tong-len has discovered the existence of 30-35 additional settlements across the state of Himachal Pradesh with an estimatead population of 9000.

The common health complaints from which displaced communities in Himachal suffer are: non-specific respiratory infections; gastro-intestinal complaints; ear, nose, throat infections and discharges; wounds; dermatological infections; anaemia; malnutrition. Common among these complaints is that all have a high prevalence among characteristically poor, urban communities, where bad housing conditions, sanitation and diet perpetuate a high incidence. They all share a common thread, however, in that their prevalence can be drastically reduced through appropriate education and lifestyle change. People suffer from respiratory infections because of the dusty, unpaved landscape, the damp housing conditions and the used of wood fires within the home. Gastrointestinal diseases come from poor hygiene practices and the use of impure water sources. Malnutrition and anaemia come from uninformed dietary choices and inequality of distribution within the household. All of this can be tackled through effective health promotion.

Aims and Objectives of the Mobile Health Unit:

In tackling the health problems, Tong-len needs to take its services to the community. This means more than just solving the logistics of getting there, it involve taking root and gaining the trust of the people, working with them progressively over time to develop a sense of change and to build the capacity of community members to take charge of their own lives. Based upon their experiences in Charan Khad, Tong-len knows that change is possible. With the establishment of a Mobile Health Unit, Tong-len could take expertise and resources to other communities to provide them with the same service which have been beneficial in Charan Khad. Its aims and objectives are 1) To expand the reach of its clinical care and health assessmenet programs; 2) To deliver improvements in the health status of all displaced populations in the Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh; 3) to improve the efficiency of Tong-len’s services in order to provide the most preferential options in health care for poor communities. Tong-len is the only organization working directly with displaced communities in Himachal Pradesh. Knowing that the health-seeking behavior of residents across these settlements is largely affected by a lack of inadequate information, gender discrimination and superstitions about medical practice,there is a real necessity for Tong-len to expand its reach. Tong-len has the expertise and established models to practice with which to do this, but requres more resources. Tong-len has already made steps in the Charan Khad settlement by providing direct clinical services and also by involving government bodies in providing sustainable programs in health promotion. If it were able to do this in other identified areas, the lasting benefits would be substantial.

For the first 6 months of the program, Tong-len aims to take services to two settlements only. While further expansion is a long-term goal, Tong-len intends to pilot its methodology with caution in two small settlements, and to monitor the feasibility of its interventions before duplicating them in other regions. This will allow the organization to adapt its existing models of education and clincal care to meet the varying needs of different populations, and will also provide it with an understanding of the logistical problems that will be new to the organization. When Tong-len has developed a thorough system for managing such outreach programs, it will expand accordingly.

Tong-len plans to begin with primary health assessments in Rajasthani communities in Paraur and Maranda, Kangra Valley, prior to implementing a program of health promotion, which will be constantly monitored and revised as necessary. The program would be taken to other displaced settlements as timing and funding permit. An annual review of the Health Unit activities will be conducted.

Immunization Awareness Stream

In addition to the continuing activities of the Mobile Health Team, Tong-len aims in Year I of the funding to conduct a one-year stream of immunization awareness and capacity building within Himachal’s displaced settlements. It has recently entered into a collaboration with the regional office of the World Health Organization to raise awareness of child immunizations among the displaced groups. Tong-len presented its current research to the Surveillance Medial Officer of the National Polio Eradication Program; it was agreed that there was a need to step-up immunization within these high-risk communities in order to check the spread of diseases such as polio. The main engine for doing this is awareness-raising through public education.

In the first two weeks of November 2006, 88 new cases of polio were registered in Uttar Pradesh. Tong-len’s research has shown that there are approximately 3,500 Uttaris resident in Himachal. That they migrate back to Uttar Prodesh places them in the high-risk category, as showing evidence of being chronically malnourished and immuno-compromised, they have a high susceptibility to the poliomyelitis virus. The Himachal Pradesh wing of the WHO Polio Eradication Program, therefore, has a duty to scale-up the immunization of these communities to prevent the poliomyelitis virus from resurfacing in Himachal. Tong-len has the capacity to assist them in this.

The Health Unit will be the ideal vehicle for doing so. There is potential for huge impact to be had by undertaking such a scheme. Currently, little awareness-raising is conducted prior to immunization sessions, and with the poorest groups–who are the most illiterate and who hold most prevalent negative myths about immunizations–this results in poor uptake of the vaccine. If Tong-len could develop a model for awareness-raising that includes elements for building the capacity of the WHO team to work more effectively with the communities, it could be adapted and scaled-up for use in other areas.

Tong-len will begin with primary health assessmentof the immunization records of the displaces settlements, and devise a program to raise awareness and build capacity with WHO units to deliver vaccine more effectively.

The Mobile Health Unit would deliver the awareness program and liaise regularly with WHO to monitor uptake of Oral Polio Vaccine, DPT, Measles and BCG vaccines within the communities.

Staffing: The program will be led and monitored by Tong-len’s Community Health Co-ordinator. Tong-len would seek to hire a trained public health worker on a one-year contract to deliver the program of education and act as a primary liaison with the WHO officials.Funding is being requested for the wages of one short-term (one year) contract liaison worker.

Monitoring: All activities will be strictly monitored under the guidelines of Tong-len’s Monitoring and Evaluation Policy. It will collect surveillance data from the WHO to monitor the impact of Tong-len’s advocacy by looking at up-take of vaccines in displaced settlements.

Methodology

As an organization, Tong-len operates a dual-stream policy for the provision of healthcare services. Stream 1 covers direct clinical care for patients with acute and chronic conditions, while Stream 2 governs the implementation of health promotion and education programs. All of its work in these areas is framed within the guidelies of its Policy for Provision of Healthcare Services. In taking work to new communities, the same guidelines would apply.

Process of implementation: Tong-len’s methodology for establishing the Mobile Health Unit is aimed at delivering sustainable change to the health profile of these communities to which it will go. Once established, the following process would be undertaken to deliver the program:

- A community would be identified as in need of support in health care;

- Tong-len staff would make an initial visit to the settlement to codnuct a primary health assessment. This would involve collecting data on the demographic make-up of the community, taking a snapshot of the main health problems–by looking at the environment and living conditions, studying the anthropometry of chldren to gage levels of malnutrition, and by identifying individuals with chronic problems–and interviewing people to gather information on health-seeking behavior;

- All of this information would be collated, and the key issues in need of address identified. From this outcome, Tong-len would design a community-specific program of education in basic health practiace, and also decide whether there is a need for clinical care to be provided by Tong-len, or whether existing health facilities in the region would be adequate;

- Following this, the Tong-len staff would begin to visit the community on a regular hasis to deliver the program of education, through seminars, one-to-one teaching, counseling and participatory appraisal. If there is a need for acute clinical care, they would take medical staff and provide a regular triage clinic with discounted medicines. From this, they would also put a support program in place for referral to local hospitals for further tests and treatment. This would be run on a means-tested basis in line with Tong-Len’s Policy of Provision of Health Services.

Mobile Health Clinic

The diesel Jeep that will serve as the mobile health clinic has been purchased. It is equipped with medical and wound care equipment as well as educational materials and some basic presentation technology.

A project nurse, Miss Radha, and a health project officer, Mr Sonam Dorjee, were hired and trained at the end of last summer. Miss Radha has eight years experience in the field.

Project Progress

The program’s services will initially be confined to the slums in the area of District Kangra. The first phase of the project is “planning and assessment.” It will be important that people who live in the slum communities learn about the Rotary project before work begins in earnest. Therefore the first few months were spent planning how to promote the services to be provided by the project. The survey system also had to be planned so that the project team could learn about the different slum communities and determine their needs.Three major surveys are planned under the categories of Population Data, General Community Information (detailing such areas as education levels and employment details) and a Health Survey (detailing information about immunization, attitudes, habits, etc.)

In September, after overcoming a number of obstacles, the projet team began visiting approximately ten slum communities to collect information and to establish contact in order to build relationships. The habits and structures within the communities were studied. Some communities have shown no apparent structure (e.g., leadership). Staff members have provided guidance to communities on such structures so as to develop a point of contact for communications.Family information was gathered and the communities’ health issues were determined. Five communities in which to offer services in the program’s initial stages were identified.

The surveys have now been completed, so the project team will be able to assess the major needs of the communities. It will then begin offering the appropriate services as it moves into the “implementation and monitoring stage. The project is a little behind schedule because the promotion and introduction phase took longer than expected since some communities were a little reluctant to welcome the group’s help as they are not familiar with Tong-len’s work. (Updated December, 2008)