Joyce Joines Newman Story

Story of the Block: Joyce Joines Newman

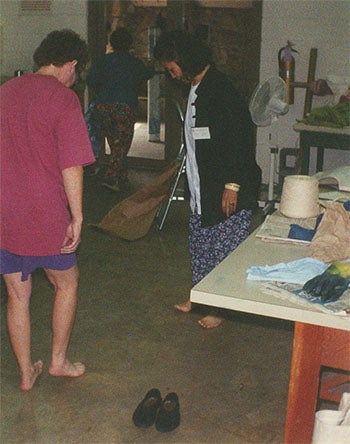

Learning to do traditional Japanese textile design techniques

In the summer of 1995 I returned to college after many years to study studio art. As part of my undergraduate coursework at UNC-Greensboro, I took a workshop at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts on the ancient craft of shibori. Shibori, also known as shaped-resist dyeing, is a Japanese term for methods of reserving and protecting areas of fabric from the dye bath that create complex patterns on the dyed cloth. A simplified version of the technique was popular for “hippie” clothing during the 1960s and 1970s as “tie dye.” Traditional methods found in Asian cultures include many other techniques for tying, stitching, folding or wrapping fabric to create resist areas, including plangi from Indonesia, bandhani from India, and tritik from Malaysia. [For more information on shibori, visit the web site of the World Shibori Network]

Fabric artists in the United States were introduced to the intricacies of traditional shibori primarily through the work of Japanese artist Yoshiko Wada and her students. [Visit web site at Yoshiko Wada] Her highly influential book, Shibori: The Inventive Art of Japanese Shaped Resist Dyeing: Tradition, Techniques, Innovation, published in 1983, remains the touchstone for resist-dye techniques. She is associated with the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, and has led worldwide textile tours. Wada was the instructor for the course at Arrowmont. Yoshiko Wada was a wonderful teacher and an amazing woman who had the rare ability to sit quietly stitching a piece of cloth and appear to be an humble domestic motherly figure, or to don a bronze pleated silk blouse and suddenly become a sophisticated cosmopolitan internationally-known artist.

Arrowmont is a contemporary craft school located in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, that derived from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century movement to establish “settlement schools” in the Southern Appalachian mountains. The purpose of these schools was to introduce educational, health care and economic opportunities for mountaineers, particularly women. Vocational education and the marketing of so-called “native crafts” was often the avenue used to provide employment and income. The founders and leaders of these schools were often privileged white New England women, often spinsters, with self-perceived altruistic motives. Yale graduate Frances Goodrich founded Allanstand Cottage Industries in Madison County in 1897 (later moved to Asheville). Olive Dame Campbell, a graduate of Tufts College, used Danish folk schools as the model for the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown. Lucy Morgan, a teacher working for the Episcopal Church, organized the Penland Weavers and Potters in 1926. Doctors Eustace and Mary Martin Sloop started the Crossnore School—a boarding school with a weaving production facility–to help mountain children “rise above” their circumstances.

Arrowmont developed from a settlement school founded in Gatlinburg in 1912 by Pi Beta Phi, the first national secret women’s college society modeled after the male Greek-letter fraternities. Pi Beta Phi had been created in 1867 and its early members were women college graduates at a time when few women were admitted to colleges or universities nationwide, let alone in Southern Appalachia. In 1926 Pi Beta Phi opened Arrowmont as an experiment in marketing handicrafts. [For a history of visit Arrowmont.] It was one of the eight crafts organizations that founded the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild in 1930 to promote the sale of “traditional” mountain crafts.

These individuals and organizations, in their fundamental perception of Southern Appalachian culture as something different and primitive that needed improvement, helped create and perpetuate myths of an isolated and backward but romantic and “pure” mountain culture that had maintained viable craft traditions, a notion that is still used today to market crafts from the area.

In the end the settlement schools and crafts organizations also served as culturally imperialistic instruments for bringing Appalachian mountaineers into mainstream American culture, not as equals with middle class Americans but in the role of workers or quaint entertainers. In some instances mountaineers were still producing “traditional” crafts, but at other times the settlement schools had to “revive” selected crafts from scratch or introduce crafts that had not been practiced historically by teaching specialized vocational skills to the mountain people. [See Weaving Day at Penland.] It was necessary to standardize craft items so that purchasers could be assured of what they would receive. Institutions such as Arrowmont “modernized” the mountaineer by introducing factory-style labor that produced standardized marketable items according to year-round strict production and shipment schedules. Cottage industry workers were required to abide by firm rules and were expected to adopt the cultural values of the settlement school leaders.

One result of the numerous and active early crafts organizations is that the Southern Appalachians today are an area rich in handcraft activities and attract large numbers of sophisticated, college trained artist craftsmen to the area. [See, for example, the Handmade in America web site.] Several of the settlement schools, notably Arrowmont and Penland School of Crafts, have survived as important nationally-recognized centers for contemporary crafts education that attract both young and old aspiring and professional craftspersons and hobbyists.

Having grown up in Appalachia, I have an ambiguous and conflicted emotional relationship to organizations such as Arrowmont and the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild for which I once worked as a folklorist. I am proud of being a mountaineer and I like traditional Appalachian culture, and I am angered by the basic assumptions behind the settlement schools and by the use of stereotypes of mountaineers to market crafts that have no relationship to that culture. I know firsthand what it’s like to be a member of a cultural minority trying to find a way to accommodate and live within the more powerful middleclass American culture, to experience daily and unendingly the cultural imperialism of that situation, and to try to retain and protect cultural values that I find superior to those of the larger culture within which I have to survive. My siblings and I jokingly but accurately say that we learned standard American English as a second language, just as we have numerous other social skills. Like members of other minorities, we are required to be culturally ambidextrous, to be able to learn and exhibit the cultural traits of the dominant culture (language, patterns of social interaction, manners, etc.) at the same time we can lapse into our own instantaneously in other environments. An example of this was when my family all gathered in Columbia, South Carolina, for my niece’s graduation from college. We attended the ceremony, dressed appropriately, behaved appropriately, clapped in the correct places, etc. Afterward, we returned to the house where she had been living with several roommates for a picnic lunch. But what attracted all of us, so that we gathered in a circle around it, was a large and luxurious patch of knee-high pokeweed growing at the side of the parking lot at the house. It would have made the finest “mess” of “poke sallet” we had had in years!

***

In many cultures, the use of shibori techniques was intimately associated with the use of indigo dye. Indigo is an ancient dye, used among other places in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Britain, Mesoamerica, Peru, Iran, and Africa. India is perhaps the oldest center of indigo dyeing, and was a primary supplier to Europe. Indigo often has strong cultural meanings, for example its evocation of the blue sea and nature in Mesopotamia, or its use for certain kinds of traditional clothing like Japanese summer Kimono or Yukata.

In order to produce a blue dye, indigo must undergo a chemical change. First it has to be dissolved; stale urine, either human or that of animals such as cows, was used traditionally. Once reduced to a soluble substance, a yellow-green solution, indigo can combine with oxygen in air and then revert to an insoluble form.

An indigo dye bath is like a living organism. To flourish it must have the proper ingredients and temperature and light conditions. If disturbed it can die. Fermentation produces bubbles on the surface and a central mound of bubbles called the “flower” that indicates the dye bath is healthy. The color is a rich iridescent mixture of yellow, green, purple, blue.

Fabric dipped in the indigo solution first turns a yellow-green, then becomes blue as it oxidizes. Watching the fabric turn to blue in the air is magical and exciting. One dipping produces only a pale blue. To create a dark blue, fabrics must be dipped repeatedly and allowed to oxidize after each dip. The most highly valued indigo textiles have been dipped so many times that they are a very dark, almost black, blue.

One of the things that impressed me most was the close association of traditional textile techniques and the natural world. If I walk along a beach in summer, I can see in the rippling patterns of sand where the waves have receded the exact source of a certain shibori technique. I am certain that the artists who developed these techniques were observing their environment closely and trying to reproduce the amazing beauty they saw there with the use of simple and humble tools–thread wound around a piece of tree trunk–and dyes made from plants. This makes me feel incredibly connected both to the craftsmen and to the world that nurtures us.